|

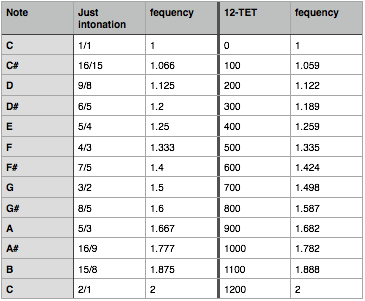

Warning: There will be math involved I recently saw a quote form a 2007 article in The Strad Magazine by Christopher Brooks that reads "Pitch and tone color are the subjective perceptions of the objective phenomenon of frequency." I love this quote. It is basically stating that notes only sound nice together because it is how we perceive it at that present moment. Intonation is not something that is set in stone. Being “in tune” changes throughout a song. There are certain instruments that are “tuned” and cannot be altered while playing like with a Piano but that does not mean that they will always be in tune with themselves. Lets take a step back and describe why something sounds in tune. All sound is created through vibrations. If a sound is vibrating at 100Hz it is vibrating 100 times every second. A note one octave above it will vibrate at 200Hz (200 times per second). Another Octave above that will vibrate a 400Hz. All of these vibrations will sound pleasant together because the sound waves match up when they hit our ear. If instead of 100Hz, 200Hz, and 400Hz we played 100Hz, 101Hz, and 199Hz, it would sound out of tune because the waves/vibrations do not match up in a way that we perceive as pleasant or harmonious. Just Intonation There are different methods of tuning. “Just intonation” uses fractions to created the intervals. If C=1 than D=9/8, E=5/4, F=4/3, G=3/2, A=5/3, B=15/8, and C and octave up=2. Because everything is based off of fractions every notes sounds in tune with the starting note C. Here is where some problems come into play though. This is an issue that occurs quite often on a string instrument like the violin, viola, cello, or double bass. Let say we are tuning our A on a violin to 432Hz. If you tune the G string perfectly with the A will be 192Hz. Now when we play an E (first finger on the D string) below the A we must have the note vibrate at 324Hz to sound good with the A string (432 x 3/4). 324Hz will not mesh very well with the G string though. If you lower it to 320Hz to sound in tune (192 x 5/3). 5:3 is a much nicer ratio than 81:48 which is what it would be if the E was still played at 324Hz You can see that the note E in this example is not set in stone. It can be both 324 or 320. Both are correct depending on what other note you are playing it with.

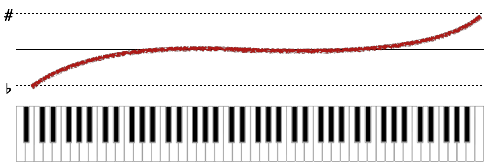

You can see that the frequencies are very similar but do vary on every single note between the octaves. Sometimes the 12-TET version is more sharp and other times it is more flat. The idea of Equal Temperament is that it is a good “middle road.” The notes will not be perfectly “in tune” with another note a large majority of the time but it creates less of an issue if you are unable to alter a pitch like on a fretted instrument like a guitar (Although you are still able to bend a pitch by pulling the string). You can see that in many ways you can say that this method has many flaws. When a piano is tuned well it will be altered as much as 30 cents from this method. The upper section of the piano will be tuned sharp while the lower end will be tuned more and more flat compared to Equal Temperament to make the piano sound more “in tune” to our ears. Beat Frequencies

If a note is close to being in tune with another note but not exact you may hear a “Beat Frequency.” I have also described this in a less scientific way as a WA-WA-WA-WA-WA sound. This occurs when the notes are a few Hz (Vibrations per second) off from sounding harmonious. If you are playing two A notes together with one is vibrating at 440Hz and the other is 441Hz you will hear one beat frequency every second. The sound is created because the amplitude of the sound wave which can simply be described as it’s volume rising when the frequencies match up. There are many other tuning systems that exist, but going down that rabbit hole is note ideal for this setting. In a nut shell, tuning can never be perfect across the board. Many compositions, especially in the Baroque era avoided certain pitches because they would clash too much to be used. Practicing scales with a tuner is a good start for beginning students to hitting close to the correct pitches but as we progress we need to adjust each individual note to be harmoniously in tune with other notes being played either by your own instrument or by those around you.

3 Comments

2/24/2015 09:14:34 am

Hi Shawn, Thanks for citing me in your site. The challenges that you point out are real; every thoughtful musician, perhaps especially violinists struggles with them. From a practical point of view, I think the best approach is to work scales, and music, with a drone, listening for pure intervals (using beats and Tartini tones). Then build from this foundation, thinking of raised leading tones, etc. as, essentially, embellishment. This approach is particularly clarifying with solo Bach. All the best.

Reply

2/24/2015 10:30:38 am

Thank you very much. I appreciate the response! I'm going to have to look more into Tartini tones now.

Reply

Simon Tagle

8/22/2016 08:03:22 pm

Tartini tones are just one of the most useful techniques for intonation! and it just makes hearing a meditative experience, as it makes you listen to the most evasive of sounds, the low resultant, and the higher(s), and so on... very happy to see that you mention it, it's a term you don't usually find people talking about. It has a section in the Oxford Companion to Music, at least in my very old edition.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

December 2016

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed